The first ten minutes of Netflix’s documentary – The Great Hack – will leave viewers with no misconceptions as to how valuable data is in the modern, globalised economy.

When Facebook was first created, people became so in love with connectivity that they didn’t bother to read the terms and conditions, ultimately resulting in companies like Cambridge Analytica, who were given the means to divide a once-connected community through manipulation and “fake news”.

The release of this documentary has, for now at least, created a stir amongst social media users about how their data is being used. Ever since the Cambridge Analytica scandal first broke, Facebook has gone to great lengths to assure its users that it’s doing more to ensure their data is safe, and used ethically.

But what has actually been done to prevent such an event from taking place again? And will it count for anything?

How it all began with Cambridge Analytica

A personality quiz on a third-party app, created by psychology professor Aleksandr Kogan, was the seed from which this scandal germinated. The app was designed as a “Personality Quiz” and collected various pieces of data from participants. But what these respondents didn’t know was that the app also gathered data on their social media friends, without their consent.

The data generated by the app was then sold to Cambridge Analytica, who were able to create highly accurate user profiles on millions of people. Facebook stated that as many as 87 million users could have been affected.

Why did Cambridge Analytica want all this data? Political clout. This database gave intimate insights into the electorate’s wants and desires, which could be targeted and influenced by their clients – namely, the Trump Presidential Campaign and the Leave Campaign in Britain’s Brexit referendum.

Cambridge Analytica claimed to have deleted the data gained through Kogan’s quiz only to have been caught still using it. This documentary really shows the scale of the impact data can have on a political campaign. Project Alamo (the campaign for Donald Trump’s presidential campaign) claimed to have 5,000 data points on every single American voter!

The impact of GDPR

When questioned by a panel of MPs on what she thought legislations should do in order to better protect people’s data and empower consumers, Brittany Kaiser (former Business Development Director of Cambridge Analytica and part of the Trump and Brexit campaign) said there was no transparent structure to allow individuals to understand what data is being collected on them or how it is being used. No permission-based structure or rights to delete.

She continued on to say that portability of data is extremely important, and that people should be allowed to monetise their data and possess their data like their property.

“Even in the European Union where your personal data is seen as property, there is not a transparent structure for you to understand what data is being collected about you, where it exists and what these data sets look like and who they are shared with or for what purposes those data are used”.

Since the subsequent scandal, a significant change has taken form in the European Union’s adoption of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). This regulation had been in development for some time prior to the Cambridge Analytica scandal, and was adopted immediately in the wake of the scandal breaking.

In keeping with the new legislation, Facebook made changes to ensure advertisers using their platform were GDPR complaint by introducing a new Pixel API to further delay the Pixel from firing until advertisers had received consent from their audience – generally gained from a cookie consent form.

What else has Facebook done?

Initially, when this scandal came to light, Facebook announced an investigation into all apps that had access to large amounts of data. Over time they announced a number of actions aimed at tightening up privacy controls and app permissions. The data given when accessing an app is now limited to name, profile photo, and email address.

In September 2018, Facebook had this to say: “In 2016, our election security efforts prepared us for traditional cyberattacks like phishing, malware, and hacking. We identified those and notified the government and those affected”. This could have led to a blind spot in Facebook’s security apparatus, where legal or semi-legal data sharing between app developers was not sufficiently scrutinized.

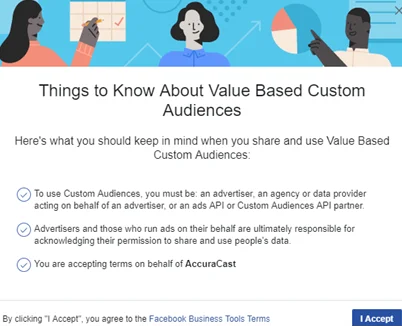

Facebook are now holding marketers and advertisers accountable by ensuring the data they use is GDPR compliant in Europe. For example, when creating a Custom Audience on Facebook (audience lists advertisers can create based on their existing first-party data), marketers are asked to accept Facebook’s business terms, as shown below.

The change is to ensure the data being imported on the platform is consensual. When creating the list, you must also confirm the original source of the data you are looking to upload.

A significant series of changes made by Facebook include their expanded efforts to protect elections and voters by removing fake accounts, limiting fake news spread on elections, and bringing transparency to political advertising. This was initially only the case for the UK, the US and Brazil and over the course of this year was expanded globally.

Although Facebook have been accused of mishandling data, Mark Zuckerberg had this to say: “We don’t sell people’s data, even though it’s often reported that we do. In fact, selling people’s information to advertisers would be counter to our business interests, because it would reduce the unique value of our service to advertisers. We have a strong incentive to protect people’s information from being accessed by anyone else”.

Conclusion

The Great Hack has ultimately helped consumers better see how their data is used and what they need to do to protect themselves. During the days of MySpace and early Facebook, users were less concerned about what was happening with their data because there simply wasn’t an understanding about what it can be used for.